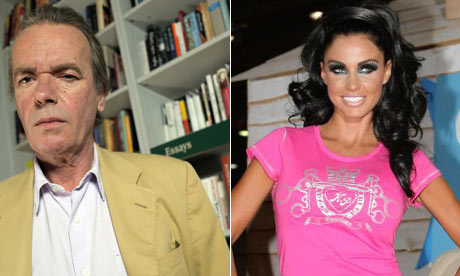

Martin Amis has never fought shy of an argument, whether it be with the critic Terry Eagleton (over Islamist extremism), his pal Christopher Hitchens (over Stalin) or fellow novelist Julian Barnes (over Amis leaving his agent – Barnes's wife).

Martin Amis has never fought shy of an argument, whether it be with the critic Terry Eagleton (over Islamist extremism), his pal Christopher Hitchens (over Stalin) or fellow novelist Julian Barnes (over Amis leaving his agent – Barnes's wife).But none of those opponents were as tough as his new target promises to be. Now 60, Amis has picked a fight with the grey power of Britain's ageing population, calling for euthanasia "booths" on street corners where they can terminate their lives with "a martini and a medal".

The author of Time's Arrow and London Fields said in an interview at the weekend that he believes Britain faces a "civil war" between young and old, as a "silver tsunami" of increasingly ageing people puts pressure on society.

"They'll be a population of demented very old people, like an invasion of terrible immigrants, stinking out the restaurants and cafes and shops," he said. "I can imagine a sort of civil war between the old and the young in 10 or 15 years' time.

"There should be a booth on every corner where you could get a martini and a medal," he added.

His comments were immediately condemned as "glib" and "offensive" by anti-euthanasia groups and those caring for the elderly and infirm. Supporters of assisted suicide, meanwhile, insisted that a dignified and compassionate end should be on offer to those who are dying.

Alistair Thompson, from the Care Not Killing Alliance, said Amis's views were "very worrying". "We are extremely disappointed that people are advocating death booths for the elderly and the disabled. How on earth can we pretend to be a civilised society if people are giving the oxygen of publicity to such proposals?

"What are these death booths? Are they going to be a kind of superloo where you put in a couple of quid and get a lethal cocktail?"

The Alzheimer's Society said there were 700,000 people with dementia in the UK and the figures were set to rise. "It is understandable that people in the early stages of dementia may reflect on the subject of euthanasia," said Andrew Ketteringham, of the Alzheimer's Society. "However, glib and offensive comments about 'euthanasia booths' and 'demented old people' only serve to alienate those dealing with this devastating condition and sidestep the hugely important question of how we can best support those affected to live well and maintain their dignity."

Amis, whose forthcoming novel, The Pregnant Widow, is due to be released shortly, stood by his comments, made in an interview in the Sunday Times.

He told the Guardian: "What we need to recognise is that certain lives fall into the negative, where pain hugely dwarfs those remaining pleasures that you may be left with. Geriatric science has been allowed to take over and, really, decency roars for some sort of correction." He said his comments were meant to be "satirical", rather than "glib".

His stance on euthanasia had hardened since the deaths of his stepfather, Lord Kilmarnock, the former SDP peer and writer, in March aged 81, and his friend Dame Iris Murdoch, the novelist, in 1999, aged 79, two years after her husband revealed that she was suffering from Alzheimer's.

"I increasingly feel that religion is so deep in our constitution and in our minds and that is something we should just peel off," he said. "Of course euthanasia is open to abuse, in that the typical grey death will be that of an old relative whose family gets rid of for one reason or another, and they'll say 'he asked me to do it', or 'he wanted to die', Amis said. "That's what we will have to look out for. Nonetheless, it is something we have to make some progress on."

Answering critics who said his comments were "offensive' to older people, Amis, a grandfather, said: "Well, I'm not a million miles away from that myself."

He added: "I had a friend who was desperately ill and she wanted to go to Switzerland, to Dignitas, but she was defeated by bureaucracy at this end. And, I think it is existentially more terrifying to feel that life is something you can't get out of.

"Frankly, I can't think of any reason for prolonging life once the mind goes. You are without dignity then."

In his interview, Amis said his stepfather had died "very horribly". "He always thought he was going to get better. But he didn't get better and I think the denial of death is a great curse."

He said Iris Murdoch, whom he had known for a very long time , was "a friend, I loved her. She was wonderful. I remember talking to her just as it started happening, and she said, 'I've entered a dark place'. That famous quote. Awareness of loss is gone, the track is gone. You don't know the day you've spent watching Teletubbies; it just vanished."

The pro-euthanasia pressure group Dignity in Dying said: "Like all too many people in the UK, Martin Amis has witnessed the bad death of a loved one." But, it added: "Dignity in Dying's campaign for a change in the law is not about the introduction of 'euthanasia booths', nor is it in anticipation of a 'silver tsunami'. Our campaign is about allowing dying adults who have mental capacity a compassionate choice to end their suffering, subject to strict legal safeguards."

--

Caroline Davies, Sunday 24 January 2010

cropped.jpg)

.jpg)

cropped.jpg)

2.jpg)

Cropped.jpg)

cropped.jpg)